|

|

|

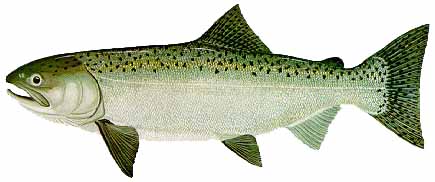

Four Runs of Chinook Salmon

![]()

Text below is excerpted from the Battle Creek Salmon and Steelhead Restoration Plan (Ward and Kier, 1999).

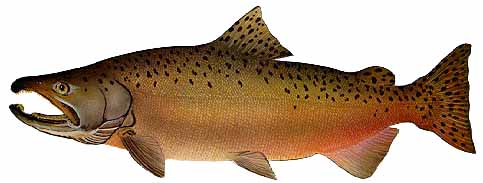

The presence of four races of chinook in Battle Creek entails a more complicated description of species life history as each of the freshwater life stages may be found in appropriate sections of Battle Creek each month of the year (Table 1). Table 1 illustrates the general timing of each run of Sacramento River chinook above Red Bluff Diversion Dam and their respective life stages. The actual timing of each life stage varies during the year and among years, primarily as a function of weather, streamflow and water temperature (Vogel and Marine 1991). Life history patterns of wild chinook have not been well documented within Battle Creek, with the exception of limited work at the turn of the century (Rutter 1903), primarily because of the low population sizes that have inhabited this stream system above CNFH during most of the Twentieth Century. Precise genetic characterization of each race of Sacramento River chinook is problematic due to the incomplete understanding of salmon genetics at this time and to suspected genetic hybridization between spring and fall-run chinook (CDFG 1993c, CDFG 1998b). For example, in the Feather River, where there is hatchery propagation of both fall-run and spring-run chinook, the operations caused hybridization (CDFG 1998); however, there are no current spring-run propagation programs on Battle Creek or the upper Sacramento River. Most distinctions between the four races of chinook salmon have been based on phenotypic traits (spawning time, run-timing, and appearance) rather than genetic differences (J. Smith, USFWS, Red Bluff, Ca., pers. comm.; CDFG 1996d). The only exception is that new analysis techniques are proving reliable for the identification of winter-run (CDFG 1998c). A complete discussion of life history stages of the four races of chinook is beyond the scope of this document. However, the following list of documents are available to provide much more detail: CDFG (1990, 1993c,1996d); Spence et al. (1996); USBR (1991, 1998a); Hallock (1971); Schafter (1980); Vogel and Marine (1991); USFWS (1997c, 1997b, 1998a); Bartholow et al. (unpubl.).

Naturally-spawning spring-run chinook enter the watershed as adults from mid-March to mid-October, though no specific peak has been observed in the run at the CNFH (Table 1; USFWS 1996a). In general, adult spring-run chinook inhabit cool pools until they spawn from late-August to mid-October (CDFG 1998b and 1996d). Emigration of juvenile spring-run is highly variable with observations ranging between spring outmigration of juveniles and fall outmigration of either yearlings or fingerlings (CDFG 1998b). Although Sacramento River spring-run have not been formally listed under ESA, their population has declined to just a few thousand wild fish in Deer Creek, Mill Creek and the mainstem Sacramento River downstream of Keswick Dam.

Adult fall-run chinook of both hatchery and naturally spawned origin migrate into the Battle Creek watershed from July through December with a peak in migration usually occurring at the CNFH barrier dam during October (Table 1; T. Parker, USFWS, Red Bluff, Ca., pers. comm.). The peak of natural spawning is early-November (CDFG 1996d) and most of the subsequent offspring leave Battle Creek by the end of June of the following year (CDFG 1990; Vogel and Marine 1991).

Naturally spawning late-fall-run chinook enter Battle Creek as adults from mid-October to mid-April and spawn from January through April with a peak in February (Table 1). The offspring of these fish leave the watershed by mid-December (CDFG 1990; Vogel and Marine 1991). The fall-run and late fall-run chinook salmon of the Sacramento River were less impacted by the construction of Shasta and Keswick Dams than the winter-run and spring-run. The spawning reaches preferred by these races are at lower elevations not blocked by dams. Also fall and late fall-run chinook also proved feasiable to culture and populations have been greatly augmented by Coleman National Fish Hatchery.

|

|

![]()

References

Moyle, P. B., R.M. Yoshiyama, and R.A. Knapp, 1996. Status of fish and fisheries. Chapter 33 of Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project: Final report to Congress. Vol. II, Assessments and scientific basis for management options. University of California, Centers for Water and Wildland Resources. Davis, CA. 21 pp. [450kb]

Ward, M. B. and W.M. Kier, 1999. Battle Creek salmon and steelhead restoration plan. Prepared for the Battle Creek Working Group by Kier Associates. Sausalito, CA . 157 pp. [1.4 Mb]

Yoshiyama, R. M., E.R. Gerstung, and F.W. Fisher, 1996. Historical and present distribution of chinook salmon in the Central Valley drainage of California. Chapter 43 of Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project: Final report to Congress. Vol. III, Assessments, Commissioned Reports and Background Information. University of California, Centers for Water and Wildland Resources. Davis, CA. 50 pp. [550kb]